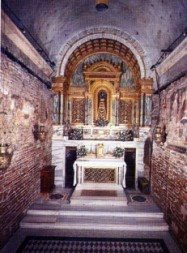

The Tomb of St Augustine

While in Canterbury I visited St Augustine's Abbey, originally founded by St Augustine and given the Roman dedication of SS Peter and Paul. Indeed Canterbury became a Kentish version of Rome, complete with a Cathedral dedicated to the Saviour - like the Lateran - and churches named after St Pancras and the Four Crowned Martyrs.

The liturgy of the early Canterbury Church attempted to imitate that of Rome – hardly surprising since St Augustine’s monks had been formed in a Roman environment. Even in the eighth century, Canterbury was still seen as a centre of chant ‘in the Roman manner’ – in 709 Bishop Acca of Hexham appointed a certain Maban as chanter, who had been trained ‘by the successors of the disciples of Gregory in Kent.’ Although no liturgical books survive, the Order of Mass was probably Roman, with a Frankish flavour, since Gregory had encouraged Augustine to adopt those practices of the Frankish Church that met with his approval. Even the early Cathedral was, in the words of the early twelfth century historian, Eadmer, ‘in some parts in imitation of the church of the blessed prince of the apostles, Peter.’ Historian Nicholas Brooks has shown that the pre-Conquest Cathedral was bi-polar in structure, so that ‘the Canterbury priest who celebrated mass at the altar of St Mary stood behind the altar and faced eastwards towards the people below, like the celebrant in the Roman basilicas.’

The Abbey became a mausoleum for the Kings of Kent and the early Archbishops of Canterbury. St Augustine's body was interred in the north porticus of the Abbey, where his immediate successors, Archbishops Mellitus, Justus, Honorius and Deusdedit, later joined him. These were unusual tombs (possibly based on contemporary Italian models), consisting of a wooden coffin placed in a pit and preserved in concrete, with the lid protruding. According to Alan Thacker, these ‘early archiepiscopal burials were envisaged as honoured graves appropriate to high ecclesiastics rather than as shrines.’ Indeed, they were arranged in a cramped space with little space for liturgical ceremonies or private pilgrim devotions.

Bede records his epitaph:

Here lies the most reverend Augustine, first archbishop of Canterbury, who was formerly sent hither by St Gregory, bishop of Rome; being supported by God in the working of miracles, he led King Ethelbert and his nation from the worship of idols to faith in Christ and ended his days of his office in peace: he died on the twenty-sixth day of May during the reign of the same king.At first St Augustine remained in the shadow of Pope Gregory and comes across as a rather colourless figure in Bede. Despite his contacts with Abbot Albinus of Canterbury, Bede may have lacked information about Augustine, but he also may have been promoting a deliberately Northumbria-centric history. Bede recognised the importance of the conversion of the Kingdom of Kent but firmly places his native Northumbria in the limelight. It is Aidan rather than Augustine, Edwin and Oswald rather than Ethelbert – in a sense York rather than Canterbury - that stands out in his History. Whenever we read early histories of the conversion of England, we need to bear in mind the rivalry with the ecclesiastical establishment at Canterbury and disputes over the Archbishop’s primacy.

They may even have a deliberate strategy in the early eighth century based not in Northumbria but at Canterbury itself that aimed to downplay the role of St Augustine and emphasise St Gregory as the apostolic evangelist of England. This fitted in with the pretensions of St Theodore who styled himself as ‘archbishop of the island of Britain.’

The cult of St Augustine only seems to have taken off from the mid eighth century. In 978 his Abbey was rededicated to ‘SS Peter and Paul and St Augustine.’ Curiously, it seems that the Normans rather the Saxons did the most to promote his cult. In 1091 the early Archbishops’ remains were solemnly translated to a new shrine inside the church – an effort on Abbot Wido’s part to unite a divided house and restate the Abbey’s ancient traditions and spiritual treasures. The event occasioned various works on Augustine and the other early Archbishops by Goscelin of Saint-Bertin, including two lives and a book of Miracles.

St Augustine’s bones were moved once again in 1221, by which time a separate reliquary contained his head. Pilgrims visited his tomb but this was always second best, compared to the glittering collection of shrines to be found in the city and, from the end of the twelfth century, the tomb of Becket. Even in the Abbey church itself, the main attraction from 1030 onwards was the shrine of St Mildred of Minster, which stood before the High Altar. Moreover, even in the writings of Goscelin, the cult is often presented in terms of the early Archbishops of Canterbury together (SS Augustine, Mellitus, Justus, Honorius and Deusdedit) rather than simply St Augustine himself. Thus the crippled eleventh century pilgrim, Leodegar, was reported to being healed after witnessing a vision of the group of Archbishops at their tombs.

St Augustine’s shrine was, of course, destroyed at the Reformation. According to Archdeacon Nicholas Harpsfield, the saint’s bones were burnt, although there is a tradition that the body was saved by Edward Thwaites (of Easture and East Stour) and moved for safekeeping to St Mary’s church at Chilham. An ancient sarcophagus with a cross on its lid is sometimes identified as St Augustine’s, although the bones have been lost.

Sorry for the recent lack of blogging - not just simply a general lack of inspiration but a hundred and one preoccupations as I get ready to move parish on 4 September. This state of affairs will continue for the next fortnight, especially since my move requires the purchase of a new computer (which I must sort out this weekend). In fact I popped over to Kingsland (my new parish) this evening to drop off some valuable items which I didn't want to entrust to the removers (such as my Napoleon III gold fiddleback, my relic collection and a rather fine C19 oil painting of Cardinal Pole - you know, the usual stuff) and was pleased to find a wireless modem waiting for me!

Sorry for the recent lack of blogging - not just simply a general lack of inspiration but a hundred and one preoccupations as I get ready to move parish on 4 September. This state of affairs will continue for the next fortnight, especially since my move requires the purchase of a new computer (which I must sort out this weekend). In fact I popped over to Kingsland (my new parish) this evening to drop off some valuable items which I didn't want to entrust to the removers (such as my Napoleon III gold fiddleback, my relic collection and a rather fine C19 oil painting of Cardinal Pole - you know, the usual stuff) and was pleased to find a wireless modem waiting for me! Before giving my talk we were treated to a tour of Christian Canterbury. It was especially good to visit St Martin's, the oldest functioning church in England. Its origins are uncertain - some say it was a Roman mausoleum and others, following St Bede, suggest it was a Romano-British church. The building is to a large extent Saxon and built on Roman foundations. It was certainly dedicated to the Gaulish St Martin by the Merovingian Queen Bertha, the wife of King St Ethelbert, and her chaplain, St Liudhard. When St Augustine and his band of forty monks arrived in Kent in 597 St Martin's became their first base and it was here that the King was probably baptised.

Before giving my talk we were treated to a tour of Christian Canterbury. It was especially good to visit St Martin's, the oldest functioning church in England. Its origins are uncertain - some say it was a Roman mausoleum and others, following St Bede, suggest it was a Romano-British church. The building is to a large extent Saxon and built on Roman foundations. It was certainly dedicated to the Gaulish St Martin by the Merovingian Queen Bertha, the wife of King St Ethelbert, and her chaplain, St Liudhard. When St Augustine and his band of forty monks arrived in Kent in 597 St Martin's became their first base and it was here that the King was probably baptised.

Some scholars argue that the hospice of San Pellegrino was initially dedicated to another St Pellegrino, a third century bishop of Auxerre who was particularly popular among French pilgrims. It is thought that a medieval carving kept at San Pellegrino shows the bishop of Auxerre blessing a pilgrim. Devotion to this saint was then linked to the local memory of a holy Irish pilgrim. Added to this were the relics of catacomb martyrs brought to Lucca in the eighth century, including a St Pellegrino, whose body may be the one venerated today at San Pellegrino in Alpe. As noted above, the relics are first mentioned in 1255 and by the sixteenth century St Pellegrino had gained a companion or disciple, St Bianco, who is not mentioned in the original versions of the legend. He is first mentioned in an Epicopal Visitation of 1559 and, sixteen years later, the bishop of Rimini is recorded as celebrating Mass in a separate chapel of St Bianco. His feast was celebrated on 3 March.

Some scholars argue that the hospice of San Pellegrino was initially dedicated to another St Pellegrino, a third century bishop of Auxerre who was particularly popular among French pilgrims. It is thought that a medieval carving kept at San Pellegrino shows the bishop of Auxerre blessing a pilgrim. Devotion to this saint was then linked to the local memory of a holy Irish pilgrim. Added to this were the relics of catacomb martyrs brought to Lucca in the eighth century, including a St Pellegrino, whose body may be the one venerated today at San Pellegrino in Alpe. As noted above, the relics are first mentioned in 1255 and by the sixteenth century St Pellegrino had gained a companion or disciple, St Bianco, who is not mentioned in the original versions of the legend. He is first mentioned in an Epicopal Visitation of 1559 and, sixteen years later, the bishop of Rimini is recorded as celebrating Mass in a separate chapel of St Bianco. His feast was celebrated on 3 March.