Marie-Antoinette

Anyway, I relaxed in the evening by accompanying Fr Richard Whinder to see Marie-Antoinette at the cinema just round the corner from the Archives. The film has had a mixed reception - the French critics at Cannes are said to have booed - but I loved it! I wasn't expecting a film with a clear beginning-middle-end nor was I looking for strict historical accuracy. But as an impressionistic portrait of a lost age, it was second to none.

Unlike any other film I've seen, you really felt as if you were there - at Versailles (and it helped, of course, that the film was shot 'on location' at the great palace). The film deserves at least Oscar nominations for costume design and photography. There were some impressive shots of the royal carriages trundling along and of the gardens of Versailles, full of courtiers as far as the eye could see. I must say Miss Dunst also cut a fine Marie-Antoinette, despite (or perhaps because of) the relative lack of dialogue. The film, I must add, was comparatively 'priest-friendly' and, with its 12A certificate, did not go down the path (which many other directors would have chosen) of including lots of sex scenes.

There were some minor irritations. Louis XV had a particularly strong, cowboy-like American accent (apologies to readers across the pond). Joseph II didn't resemble the obsessively enlightened despot that he was. The modern rock music (juxtaposed with the odd Baroque aria) didn't always work as a soundtrack. And - as always with big films - there were numerous liturgical errors in the ceremonial scenes, such as cardinals wearing chasubles under their copes (unless it was an ancient Gallican privilege?!). This is particularly tragic because the Versailles area is not short of a few traditionalist clergy who could have advised on such matters.

Worst of all, in my mind, is the fact the film stops at the Revolution, which was the Queen's finest hour. As Elena Maria Vidal (Catholic author of such novels as Trianon) has pointed out:

The Coppola film ends when the Revolution begins, at the moment when Marie-Antoinette came into her own as the daughter of a great empress and as a queen who would not forsake her husband or her duty, even when to do so cost her her life. The new generation of movie goers will be deprived of such an inspiration that would be so powerful on screen. Antoinette's Christian fortitude is ignored and her personal tragedy is trivialized amid a movie of froth. Without the spiritual depths, the depiction is shallow and incomplete.

However, at least Marie-Antoinette is very much the heroine and, in its quiet way, the film is a piece of historical revision and goes against the traditional 'let them eat cake' image of the French Queen (although the 'myth' of her affair with Count Axel von Fersen is repeated). For a historical critique of the film, see Elena Maria Vidal's website (raised biretta to Dappled Things). But, on the whole, the film gets a thumbs up from the Roman Miscellanist.

(All pictures copyright Columbia Pictures)

St Amphibalus (whose name possibly derived from the Greek name given to a cloak) appeared in the twelfth century as a martyr in his own right. According to William the Monk’s largely fanciful Alia Acta SS Albani et Amphibali et Sociorum (‘Other Doings of SS Alban and Amphibalus and their Companions’) St Amphibalus fled to Wales together with a thousand converts he had made at Verulamium. Eventually they were discovered by the pagans and massacred. Two members of this multitude of early British martyrs were given the names of SS Socrates and Stephanos (Feast: 17 September). I must confess I had never heard of them until today. St Amphibalus was eventually taken back to Verulamium in chains and disembowelled, scourged, stabbed and finally stoned to death.

St Amphibalus (whose name possibly derived from the Greek name given to a cloak) appeared in the twelfth century as a martyr in his own right. According to William the Monk’s largely fanciful Alia Acta SS Albani et Amphibali et Sociorum (‘Other Doings of SS Alban and Amphibalus and their Companions’) St Amphibalus fled to Wales together with a thousand converts he had made at Verulamium. Eventually they were discovered by the pagans and massacred. Two members of this multitude of early British martyrs were given the names of SS Socrates and Stephanos (Feast: 17 September). I must confess I had never heard of them until today. St Amphibalus was eventually taken back to Verulamium in chains and disembowelled, scourged, stabbed and finally stoned to death.

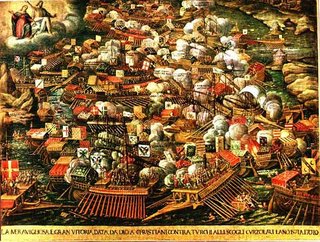

On 7 October 1571 the forces of Christendom, under the command of Don Juan, defeated the Turks at Lepanto. The famous sea victory was attributed to the intercession of the Blessed Virgin because the Rosary had been recited both by the soldiers before battle and by many of the faithful in Rome. St Pius V instituted the Feast of Our Lady of Victories and, shortly afterwards, Gregory XIII changed this to Our Lady of the Rosary. In the early eighteenth century, following some further victories against the Turks, the Feast was extended throughout the Church. And so October became known as the month of the Holy Rosary.

On 7 October 1571 the forces of Christendom, under the command of Don Juan, defeated the Turks at Lepanto. The famous sea victory was attributed to the intercession of the Blessed Virgin because the Rosary had been recited both by the soldiers before battle and by many of the faithful in Rome. St Pius V instituted the Feast of Our Lady of Victories and, shortly afterwards, Gregory XIII changed this to Our Lady of the Rosary. In the early eighteenth century, following some further victories against the Turks, the Feast was extended throughout the Church. And so October became known as the month of the Holy Rosary.

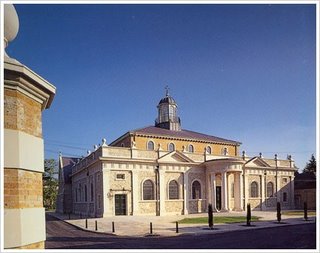

The neo-classical architecture is undoubtedly tasteful but it seems strange that the most prominent decorative feature of the church interior are the massive golden chandeliers - prominent because there is hardly any other decoration. It took me some time to notice the presence of the cross; there are very few images and the stations (the roundels above the arches) are in a modern style and very hard to make out.

The neo-classical architecture is undoubtedly tasteful but it seems strange that the most prominent decorative feature of the church interior are the massive golden chandeliers - prominent because there is hardly any other decoration. It took me some time to notice the presence of the cross; there are very few images and the stations (the roundels above the arches) are in a modern style and very hard to make out.